Chapter 2 Information

Effective information management must begin by thinking about how people use information—not with how people use machines.

Davenport, T. H. (1994). Saving IT’s soul: human-centered information management. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 119-131.

Learning objectives

Students completing this chapter will

understand the importance of information to society and organizations;

be able to describe the various roles of information in organizational change;

be able to distinguish between soft and hard information;

know how managers use information;

be able to describe the characteristics of common information delivery systems;

distinguish the different types of knowledge.

Introduction

There are three characteristics of the first two decades of the twenty-first century: global warming, high-velocity global change, and the emerging power of information organizations.7 The need to create a sustainable civilization, the globalization of business, and the rise of China as a major economic power are major forces contributing to mass change. Organizations are undergoing large-scale restructuring as they attempt to reposition themselves to survive the threats and exploit the opportunities presented by these changes.

This century, some very powerful and highly profitable information-based organizations have emerged. In 20212, Apple and Microsoft vied to be the world’s largest company in terms of market value. Leveraging the iPhone and IOS, Apple has shown the power of information services to change an industry. Google has become a well-known global brand as it fulfills its mission “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Amazon is disrupting traditional retail. Facebook has digitized our social world, and Microsoft has dominated the office environment for decades. We gain further insights into the value of information by considering its role in civilization.

A historical perspective

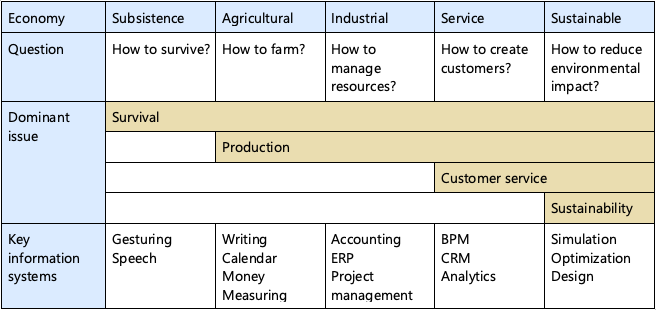

Humans have been collecting data to manage their affairs for several thousand years. In 3000 BCE, Mesopotamians recorded inventory details in cuneiform, an early script. Today’s society transmits Exabytes of data every day as billions of people and millions of organizations manage their affairs. The dominant issue facing each type of economy has changed over time, and the collection and use of data has changed to reflect these concerns, as shown in the following table.

Societal focus

Agrarian society was concerned with productive farming, and an important issue was when to plant crops. Ancient Egypt, for example, based its calendar on the flooding of the Nile. The focus shifted during the industrial era to management of resources (e.g., raw materials, labor, logistics). Accounting, ERP, and project management became key information systems for managing resources. In the current service economy, the focus has shifted to customer creation. There is an oversupply of many consumer products (e.g., cars) and companies compete to identify services and product features that will attract customers. They are concerned with determining what types of customers to recruit and finding out what they want. As a result, we have seen the rise of business analytics and customer relationship management (CRM) to address this dominant issue. As well as creating customers, firms need to serve those already recruited. High quality service often requires frequent and reliable execution of multiple processes during manifold encounters with customers by a firm’s many customer facing employees (e.g., a quick service restaurant, an airline, a hospital). Consequently, business process management (BPM) has grown in importance since the mid 1990s when there was a surge of interest in business process reengineering.

We are in transition to a new era, sustainability, where attention shifts to assessing environmental impact because, after several centuries of industrialization, atmospheric CO2 levels have become alarmingly high. We are also exceeding the limits of the planet’s resources as global population nears eight billion people. As a result, a new class of application is emerging, such as environmental management systems and UPS’s telematics project.8 These new systems will also include, for example, support for understanding environmental impact through simulation of energy consumption and production systems, optimization of energy systems, and design of low impact production and customer service systems. Notice that dominant issues don’t disappear but rather aggregate in layers, so today’s business will be concerned with survival, production, customer service, and sustainability. As a result, a firm’s need for data never diminishes, and each new layer creates another set of data needs. The flood will not subside and for most firms the data flow will need to grow significantly to meet the new challenge of sustainability.

A constant across all of these economies is organizational memory, or in its larger form, social memory. Writing and paper manufacturing developed about the same time as agricultural societies. Limited writing systems appeared about 30,000 years ago. Full writing systems, which have evolved in the last 5,000 years, made possible the technological transfer that enabled humanity to move from hunting and gathering to farming. Writing enables the recording of knowledge, and information can accumulate from one generation to the next. Before writing, knowledge was confined by the limits of human memory.

There is a need for a technology that can store knowledge for extended periods and support the transport of written information. Storage medium has advanced from clay tablets (4000 BCE), papyrus (3500 BCE), and parchment (2000 BCE) to paper (100 CE). Written knowledge gained great impetus from Johannes Gutenberg, whose achievement was a printing system involving movable metal type, ink, paper, and press. In less than 50 years, printing technology diffused throughout most of Europe. In the last century, a range of new storage media appeared (e.g., photographic, magnetic, and optical).

Organizational memories emerged with the development of large organizations such as governments, armies, churches, and trading companies. The growth of organizations during the industrial revolution saw a massive increase in the number and size of organizational memories. This escalation continued throughout the twentieth century.

The Internet has demonstrated that we now live in a borderless world. There is a free flow of information, investment, and industry across borders. Customers ignore national boundaries to buy products and services. In the borderless information age, the old ways of creating wealth have been displaced by intelligence, marketing, global reach, and education. Excelling in the management of data, information, and knowledge has become a prerequisite for corporate and national wealth.

Wealth creation

| The old | The new |

|---|---|

| Military power | Intelligence |

| Natural resources | Marketing |

| Population | Global reach |

| Industry | Education |

This brief history shows the increasing importance of information. Civilization was facilitated by the discovery of means for recording and disseminating information. In our current society, organizations are the predominant keepers and transmitters of information.

A brief history of information systems

Information systems has three significant eras. In the first era, information work was transported to the computer. For instance, a punched card deck was physically transported to a computer center, the information was processed, and the output physically returned to the worker as a printout.

Information systems eras

| Era | Focus | Period | Technology | Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Take information work to the computer | 1950s – mid-1970s | Batch | Few data networks |

| 2 | Take information work to the employee | Mid-1970s – mid-1990s | Host/terminal Client/server | Spread of private networks |

| 3 | Take information work to the customer and other stakeholders | Mid-1990s – present | Browser/server | Public networks (Internet) |

In the second era, private networks were used to take information work to the employee. Initially, these were time-sharing and host/terminal systems. IS departments were concerned primarily with creating systems for use by an organization’s employees when interacting with customers (e.g., a hotel reservation system used by call center employees) or for the employees of another business to transact with the organization (e.g., clerks in a hospital ordering supplies).

Era 3 starts with the appearance of the Web browser in the mid-1990s. The browser, which can be used on the public and global Internet, permits organizations to take information and information work to customers and other stakeholders. Now, the customer undertakes work previously done by the organization (e.g., making an airline reservation).

The scale and complexity of era 3 is at least an order of magnitude greater than that of era 2. Nearly every company has far more customers than employees. For example, UPS, with an annual investment of billions in information systems and over 500,000 employees, is one of the world’s largest employers. However, there are over 11 million customers, over 20 times the number of employees, who are electronically connected to UPS.

Era 3 introduced direct electronic links between a firm and its stakeholders, such as investors and citizens. In the earlier eras, intermediaries often communicated with stakeholders on behalf of the firm (e.g., a press release to the news media). These messages could be filtered and edited, or sometimes possibly ignored, by intermediaries. Now, organizations can communicate directly with their stakeholders via the Web, e-mail, social media. Internet technologies offer firms a chance to rethink their goals vis-à-vis each stakeholder class and to use Internet technology to pursue these goals.

This brief history leads to the conclusion that the value IS creates is determined by whom an organization can reach, how it can reach them, and where and when it can reach them.

Who. Who an organization can contact determines whom it can influence, inform, or transfer work to. For example, if a hotel can be contacted electronically by its customers, it can promote online reservations (transfer work to customers), and reduce its costs.

How. How an organization reaches a stakeholder determines the potential success of the interaction. The higher the bandwidth of the connection, the richer the message (e.g., using video instead of text), the greater the amount of information that can be conveyed, and the more information work that can be transferred.

Where. Value is created when customers get information directly related to their current location (e.g., a navigation system) and what local services they want to consume (e.g., the nearest Italian restaurant).

When. When a firm delivers a service to a client can greatly determine its value. Stockbrokers, for instance, who can inform clients immediately of critical corporate news or stock market movements are likely to get more business.

Information characteristics

Three useful concepts for describing information are hardness, richness, and class. Information hardness is a subjective measure of the accuracy and reliability of an item of information. Information richness describes the concept that information can be rich or lean depending on the information delivery medium. Information class groups types of information by their key features.

Information hardness

In 1812, the Austrian mineralogist Friedrich Mohs proposed a scale of hardness, in order of increasing relative hardness, based on 10 common minerals. Each mineral can scratch those with the same or a lower number, but cannot scratch higher-numbered minerals.

A similar approach can be used to describe information. Market information, such as the current price of gold, is the hardest because it is measured extremely accurately. There is no ambiguity, and its measurement is highly reliable. In contrast, the softest information, which comes from unidentified sources, is rife with uncertainty.

An information hardness scale

| Mineral | Scale | Data |

|---|---|---|

| Talc | 1 | Unidentified source—rumors, gossip, and hearsay |

| Gypsum | 2 | Identified non-expert source—opinions, feelings, and ideas |

| Calcite | 3 | Identified expert source—predictions, speculations, forecasts, and estimates |

| Fluorite | 4 | Unsworn testimony—explanations,justifications, assessments, and justifications, assessments, and interpretations |

| Apatite | 5 | Sworn testimony—explanations, justifications, assessments, and interpretations |

| Orthoclase | 6 | Budgets, formal plans |

| Quartz | 7 | News reports, non-financial data, industry statistics, and surveys |

| Topaz | 8 | Unaudited financial statements, and government statistics |

| Corundum | 9 | Audited financial statements |

| Diamond | 1 0 | Stock exchange and commodity market data |

Audited financial statements are in the corundum zone. They are measured according to standard rules (known as “generally accepted accounting principles”) that are promulgated by national accounting societies. External auditors monitor the application of these standards, although there is generally some leeway in their application and sometimes multiple standards for the same item. The use of different accounting principles can lead to different profit and loss statements. As a result, the information in audited financial statements has some degree of uncertainty.

There are degrees of hardness within accounting systems. The hardest data are counts, such as units sold or customers served. These are primary measures of organizational performance. Secondary measures, such as dollar sales and market share, are derived from counts. Managers vary in their preference for primary and secondary measures. Operational managers opt for counts for measuring productivity because they are uncontaminated by price changes and currency fluctuations. Senior managers, because their focus is on financial performance, select secondary measures.

The scratch test provides a convenient and reliable method of assessing the hardness of a mineral. Unfortunately, there is no scratch test for information. Managers must rely on their judgment to assess information hardness.

Although managers want hard information, there are many cases when it is not available from a single source. They compensate by seeking information from several different places. Relatively consistent information from multiple sources is reassuring.

Information richness

Information can be described as rich or lean. It is richest when delivered face-to-face. Conversation permits immediate feedback for verification of meaning. You can always stop the other speaker and ask, “What do you mean?” Face-to-face information delivery is rich because you see the speaker’s body language, hear the tone of voice, and natural language is used. A numeric document is the leanest form of information. There is no opportunity for questions, no additional information from body movements and vocal tone. The information richness of some communication media is shown in the following table.

Information richness and communication media9

| Richest | Leanest | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-face | Telephone | Personal documents | Impersonal documents | Numeric documents |

Managers seek rich information when they are trying to resolve equivocality or ambiguity, which means that managers cannot make sense of a situation because they arrive at multiple, conflicting interpretations of the information. An example of an equivocal situation is a class assignment where some of the instructions are missing and others are contradictory (of course, this example is an extremely rare event).

Equivocal situations cannot be resolved by collecting more information, because managers are uncertain about what questions to ask and often a clear answer is not possible. Managers reduce equivocality by sharing their interpretations of the available information and reaching a collective understanding of what the information means. By exchanging opinions and recalling their experiences, they try to make sense of an ambiguous situation.

Many of the situations that managers face each day involve a high degree of equivocality. Formal organizational memories, such as databases, are not much help, because the information they provide is lean. Many managers rely far more on talking with colleagues and using informal organizational memories such as social networks.

Data management is almost exclusively concerned with administering the formal information systems that deliver lean information. Although this is their proper role, data managers must realize that they can deliver only a portion of the data required by decision makers.

Information classes

Information can be grouped into four categories: content, form, behavior, and action. Until recently, most organizational information fell into the first class.

Information classes

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| Content | Quantity, location, and types of items |

| Form | Shape and composition of an object |

| Behavior | Simulation of a physical object |

| Action | Creation of action (e.g., industrial robots) |

Content information records details about quantity, location, and types of items. It tends to be historical in nature and is traditionally the class of information collected and stored by organizations. The content information of a car would describe its model number, color, price, options, horsepower, and so forth. Hundreds of bytes of data may be required to record the full content information of a car. Typically, content data are captured by a TPS.

Form information describes the shape and composition of an object. For example, the form information of a car would define the dimensions and composition of every component in it. Millions of bytes of data are needed to store the form of a car. CAD/CAM systems are used to create and store form information.

Behavior information is used to predict the responses of a physical object using simulation techniques. Such systems typically require a combination of input data and mathematical equations. Massive numbers of calculations per second are required to simulate behavior. For example, simulating the flight of a new aircraft design may require trillions of computations. Behavior information is often presented visually because the vast volume of data generated cannot be easily processed by humans in other formats.

Action information enables the instantaneous creation of sophisticated action. Industrial robots take action information and manufacture parts, weld car bodies, or transport items. Antilock brakes are an example of action information in use.

Information and organizational change

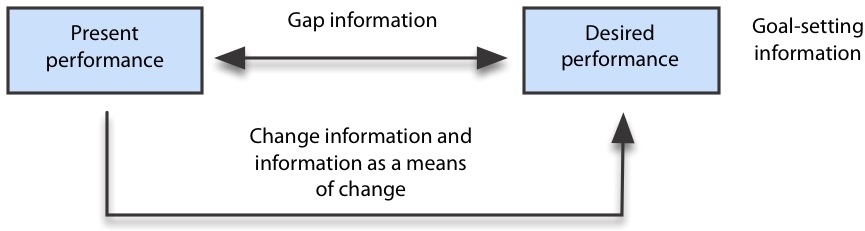

Organizations are goal-directed. They undergo continual change as they use their resources, people, technology, and financial assets to reach some future desired outcome. Goals are often clearly stated, such as to make a profit of USD 100 million, win a football championship, or decrease the government deficit by 25 percent in five years. Goals are often not easily achieved, however, and organizations continually seek information that supports goal attainment. The information they seek falls into three categories: goal setting, gap, and change.

Organizational information categories

The emergence of an information society also means that information provides dual possibilities for change. Information is used to plan change, and information is a medium for change.

Goal-setting information

Organizations set goals or levels of desired performance. Managers need information to establish goals that are challenging but realistic. A common approach is to take the previous goal and stretch it. For example, a company with a 15 percent return on investment (ROI) might set the new goal at 17 percent ROI. This technique is known as “anchoring and adjusting.” Prior performance is used as a basis for setting the new performance standards. The problem with anchoring and adjusting is that it promotes incremental improvement rather than radical change because internal information is used to set performance standards. Some organizations have turned to external information and are using benchmarking as a source of information for goal setting.

Planning

Planning is an important task for senior managers. To set the direction for the company, they need information about consumers’ potential demands and social, economic, technical, and political conditions. They use this information to determine the opportunities and threats facing the organization, thus permitting them to take advantage of opportunities and avoid threats.

Most of the information for long-term planning comes from sources external to the company. There are think tanks that analyze trends and publish reports on future conditions. Journal articles and books can be important sources of information about future events. There will also be a demand for some internal information to identify trends in costs and revenues. Major planning decisions, such as building a new plant, will be based on an analysis of internal data (use of existing capacity) and external data (projected customer demand).

Benchmarking

Benchmarking establishes goals based on best industry practices. It is founded on the Japanese concept of dantotsu, striving to be the best of the best. Benchmarking is externally directed. Information is sought on those companies, regardless of industry, that demonstrate outstanding performance in the areas to be benchmarked. Their methods are studied, documented, and used to set goals and redesign existing practices for superior performance.

Other forms of external information, such as demographic trends, economic forecasts, and competitors’ actions can be used in goal setting. External information is valuable because it can force an organization to go beyond incremental goal setting.

Organizations need information to identify feasible, motivating, and challenging goals. Once these goals have been established, they need information on the extent to which these goals have been attained.

Gap information

Because goals are meant to be challenging, there is often a gap between actual and desired performance. Organizations use a number of mechanisms to detect a gap and gain some idea of its size. Problem identification and scorekeeping are two principal methods of providing gap information.

Problem identification

Business conditions are continually changing because of competitors’ actions, trends in consumer demand, and government actions. Often these changes are reflected in a gap between expectations and present performance. This gap is often called a problem.

To identify problems, managers use exception reports, which are generated when conditions vary from the established goal or standard. Once a potential problem has been identified, managers collect additional information to confirm that a problem really exists. Once management has been alerted, the information delivery system needs to shift into high gear. Managers will request rapid delivery of ad hoc reports from a variety of sources. The ideal organizational memory system can adapt smoothly to deliver appropriate information quickly.

Scorekeeping

Keeping track of the score provides gap information. Managers ask many questions: How many items did we make yesterday? What were the sales last week? Has our market share increased in the last year? They establish measurement systems to track variables that indicate whether organizational performance is on target. Keeping score is important; managers need to measure in order to manage. Also, measurement lets people know what is important. Once a manager starts to measure something, subordinates surmise that this variable must be important and pay more attention to the factors that influence it.

There are many aspects of the score that a manager can measure. The overwhelming variety of potentially available information is illustrated by the sales output information that a sales manager could track. Sales input information (e.g., number of service calls) can also be measured, and there is qualitative information to be considered. Because of time constraints, most managers are forced to limit their attention to 10 or fewer key variables singled out by the critical success factors (CSF) method.10 Scorekeeping information is usually fairly stable.

Sales output tracking information

| Category | Example |

|---|---|

| Orders | Number of current customers |

| Average order size | |

| Batting average (orders to calls) | |

| Sales volume | Dollar sales volume |

| Unit sales volume | |

| By customer type | |

| By product category | |

| Translated to market share | |

| Quota achieved | |

| Margins | Gross margin |

| Net profit | |

| By customer type | |

| By product | |

| Customers | Number of new accounts |

| Number of lost accounts | |

| Percentage of accounts sold | |

| Number of accounts overdue | |

| Dollar value of receivables | |

| Collections of receivables |

Change information

Accurate change information is very valuable because it enables managers to predict the outcome of various actions to close a gap with some certainty. Unfortunately, change information is usually not very precise, and there are many variables that can influence the effect of any planned change. Nevertheless, organizations spend a great deal of time collecting information to support problem solving and planning.

Problem solution

Once a concern has been identified, a manager seeks to find its cause. A decrease in sales could be the result of competitors introducing a new product, an economic downturn, an ineffective advertising campaign, or many other reasons. Data can be collected to test each of these possible causes. Additional data are usually required to support analysis of each alternative. For example, if the sales decrease has been caused by an economic recession, the manager might use a decision support system (DSS) to analyze the effect of a price decrease or a range of promotional activities.

Information as a means of change

The emergence of an information society means that information can be used as a means of changing an organization’s performance. Corporations can create information-based products and services, adding information to products, and using information to enhance existing performance or gain a competitive advantage. Further insights into the use of information as a change agent are gained by examining marketing, customer service, and empowerment.

Marketing

Marketing is a key strategy for changing organizational performance by increasing sales. Information has become an important component in marketing. Airlines and retailers have established frequent flyer and buyer programs to encourage customer loyalty and gain more information about customers. These systems are heavily dependent on database technology because of the massive volume of data that must be stored. Indeed, without database technology, some marketing strategies could never be implemented.

Database technology offers the opportunity to change the very nature of communications with customers. Broadcast media have been the traditional approach to communication. Advertisements are aired on television, placed in magazines, or displayed on a Web site. Database technology can be used to address customers directly. No longer just a mailing list, today’s database can be a memory of customer relationships, a record of every message and response between the firm and a customer. Some companies keep track of customers’ preferences and customize advertisements to their needs. Leading online retailers now send customers only those emails for products for which they estimate there is a high probability of a purchase. For example, a customer with a history of streaming jazz music is sent an email promoting a jazz concert in their city.

The Web has significantly enhanced the value of database technology. Many firms now use a combination of a Web site and a DBMS to market products and service customers.

Customer Service

Many business leaders consider customer service as a critical goal for organizational success. Many of the developed economies are service driven. In the United States, services account for nearly 80 percent of the GNP and most of the new jobs. Many companies now compete for customers by offering superior customer service. Information is frequently a key to this improved service.

❓ Skill builder

For many businesses, information is the key to high-quality customer service. Some firms use information, and thus customer service, as a key differentiating factor, while others might compete on price. Compare the electronics component of Web sites Amazon and Walmart. How do they use price and information to compete? What are the implications for data management if a firm uses information to compete?

Empowerment

Empowerment means giving employees greater freedom to make decisions. More precisely, it is sharing with frontline employees

information about the organization’s performance;

rewards based on the organization’s performance;

knowledge and information that enable employees to understand and contribute to organizational performance;

power to make decisions that influence organizational direction and performance.

Notice that information features prominently in the process. A critical component is giving employees access to the information they need to perform their tasks with a high degree of independence and discretion. Information is empowerment. By linking employees to organizational memory, data managers play a pivotal role in empowering people. Empowerment can contribute to organizational performance by increasing the quality of products and services. Together, empowerment and information are mechanisms of planned change.

Information and managerial work

Because managers frequently use data management systems in their normal activities as a source of information about change and as a means of implementing change, it is crucial for systems designers to understand how managers work. Failure to take account of managerial behavior can result in a system that is technically sound but rarely used because it does not fit the social system.

Studies over several decades reveal a very consistent pattern: Managerial work is very fragmented. Managers spend an average of 10 minutes on any task, and their day is organized into brief periods of concentrated attention to a variety of tasks. They work unrelentingly and are frequently interrupted by unexpected disturbances. Managers are action oriented and rely on intuition and judgment far more than contemplative analysis of information.

Managers strongly prefer oral communication. They spend a great deal of time conversing directly or by telephone. Managers use interpersonal communication to establish networks and build social capital, which they later use as a source of information and a way to influence outcomes. The continual flow of verbal information helps them make sense of events and lets them feel the organizational pulse.

Managers rarely use formal reporting systems. They do not spend a lot of time analyzing computer reports or querying databases but resort to formal reports to confirm impressions, should interpersonal communications suggest there is a problem. Even when managers are provided with a purpose-built, ultra-friendly executive information system, their behavior changes very little. They may access a few screens during the day, but oral communication is still their preferred method of data gathering and dissemination.

Managers’ information requirements

Managers have certain requirements of the information they receive. These expectations should shape a data management system’s content and how data are processed and presented.

Managers expect to receive information that is useful for their current task under existing business conditions. Unfortunately, managerial tasks can change rapidly. The interlinked, global, economic environment is highly turbulent. Since managers’ expectations are not stable, the information delivery system must be sufficiently flexible to meet changing requirements.

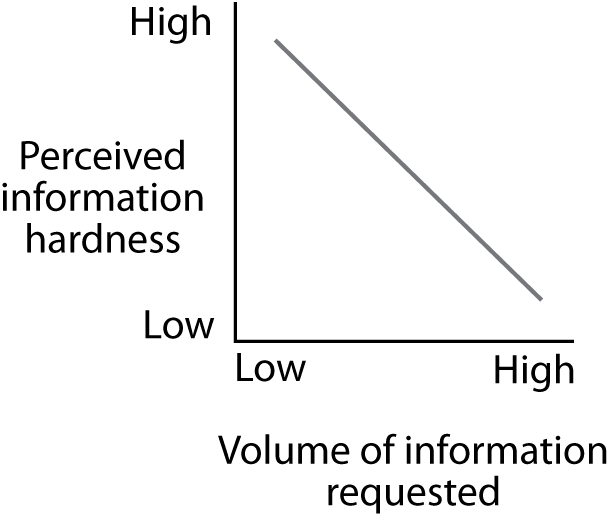

Managers’ demands for information vary with their perception of its hardness; they require only one source that scores 10 on the information hardness scale. The Nikkei Index at the close of today’s market is the same whether you read it in the Asian Wall Street Journal or The Western Australian or hear it on CNN. As perceived hardness decreases, managers demand more information, hoping to resolve uncertainty and gain a more accurate assessment of the situation. When the reliability of a source is questionable, managers seek confirmation from other sources. If a number of different sources provide consistent information, a manager gains confidence in the information’s accuracy.

Relationship of perceived information hardness to volume of information requested

It is not unusual, therefore, to have a manager seek information from a database, a conversation with a subordinate, and a contact in another organization. If a manager gets essentially the same information from each source, they have the confirmation they sought. This means each data management system should be designed to minimize redundancy, but different components of organizational memory can supply overlapping information.

Managers’ needs for information vary accordingly with responsibilities

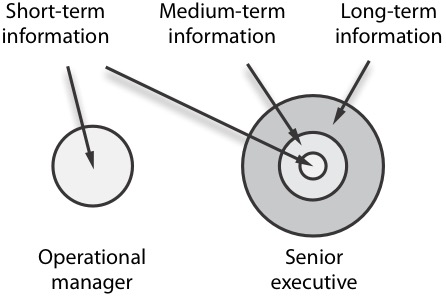

Operational managers need detailed, short-term information to deal with well-defined problems in areas such as sales, service, and production. This information comes almost exclusively from internal sources that report recent performance in the manager’s area. A sales manager may get weekly reports of sales by each direct report.

As managers move up the organizational hierarchy, their information needs both expand and contract. They become responsible for a wider range of activities and are charged with planning the future of the organization, which requires information from external sources on long-term economic, demographic, political, and social trends. Despite this long-term focus, top-level managers also monitor short-term, operational performance. In this instance, they need less detail and more summary and exception reports on a small number of key indicators. To avoid information overload as new layers of information needs are added, the level of detail on the old layers naturally must decline, as illustrated in the following figure.

Management level and information need

Information satisficing

Because managers face making many decisions in a short period, most do not have the time or resources to collect and interpret all the information they need to make the best decision. Consequently, they are often forced to satisfice. That is, they accept the first satisfactory decision they discover. They also satisfice in their information search, collecting only enough information to make a satisfactory decision.

Ultimately, information satisficing leads to lower-quality decision making. If, however, information systems can accelerate delivery and processing of the right information, then managers should be able to move beyond selecting the first satisfactory decision to selecting the best of several satisfactory decisions.

Information delivery systems

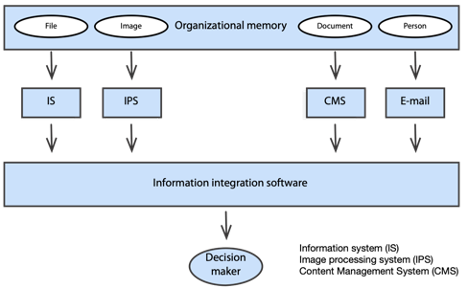

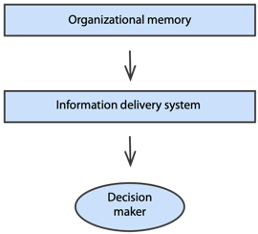

Most organizations have a variety of delivery systems to provide information to managers. Developed over many years, these systems are integrated, usually via a Web site, to give managers better access to information. There are two aspects to information delivery. First, there is a need for software that accesses an organizational memory, extracts the required data, and formats it for presentation. We can use the categories of organizational memories introduced in Chapter 1 to describe the software side of information delivery systems. The second aspect of delivery is the hardware that gets information from a computer to the manager.

Information delivery systems software

| Organizational memory | Delivery systems |

|---|---|

| People | Conversation |

| Meeting | |

| Report | |

| Groupware | |

| Documents | Web browser |

| E-mail attachment | |

| Images | Image processing system (IPS) |

| Graphics | Computer aided design (CAD) |

| Geographic information system (GIS) | |

| Voice | Voice mail |

| Voice recording system | |

| Mathematical model | Decision support system (DSS) |

| Decisions | Conversation |

| Meeting | |

| Report | |

| Groupware |

Software is used to move data to and from organizational memory. There is usually tight coupling between software and the format of an organizational memory. For example, a relational database management system can access tables but not decision-support models. This tight coupling is particularly frustrating for managers who often want integrated information from several organizational memories. For example, a sales manager might expect a monthly report to include details of recent sales (from a relational database) to be combined with customer comments (from email messages to a customer service system). A quick glance at the preceding table shows that there are many different information delivery systems. We will discuss each of these briefly to illustrate the lack of integration of organizational memories.

Verbal exchange

Conversations, meetings, and oral reporting are commonly used methods of information delivery. Indeed, managers show a strong preference for verbal exchange as a method for gathering information. This is not surprising because we are accustomed to oral information. This is the way we learned for thousands of years as a preliterate culture. Only recently have we learned to make decisions using computer reports and visuals.

Voice mail

Voice mail is useful for people who do not want to be interrupted. It supports asynchronous communication; that is, the two parties to the conversation are not simultaneously connected. Voice-mail systems also can store many prerecorded messages that can be selectively replayed using a phone’s keypad. Organizations use this feature to support standard customer queries.

Electronic mail

Email is an important system of information delivery. It too supports asynchronous messaging, and it is less costly than voice mail for communication. Many documents are exchanged as attachments to email.

Formal report

Formal reports have a long history in organizations. Before electronic communication, they were the main form of information delivery. They still have a role in organizations because they are an effective method of integrating information of varying hardness and from a variety of organizational memories. For example, a report can contain text, tables, graphics, and images.

Formal reports are often supplemented by a verbal presentation of the key points in the report. Such a presentation enhances the information delivered, because the audience has an opportunity to ask questions and get an immediate response.

Meetings

Because managers spend 30-80 percent of their time in meetings, these are a key source of information.

Groupware

Since meetings occupy so much managerial time and in many cases are poorly planned and managed, organizations are looking for improvements. Groupware is a general term applied to a range of software systems designed to improve some aspect of group work. It is excellent for tapping soft information and the informal side of organizational memory.

Image processing system

An image processing system (IPS) captures data using a scanner to digitize an image. Images in the form of letters, reports, illustrations, and graphics have always been an important type of organizational memory. An IPS permits these forms of information to be captured electronically and disseminated.

Computer-aided design

Computer-aided design (CAD) is used extensively to create graphics. For example, engineers use CAD in product design, and architects use it for building design. These plans are a part of organizational memory for designers and manufacturers.

Information integration

A fundamental problem for most organizations is that their memory is fragmented across a wide variety of formats and technologies. Sometimes, there is a one-to-one correspondence between an organizational memory for a particular functional area and the software delivery system. For example, sales information is delivered by the sales system and production information by the production system. This is not a very desirable situation because managers want all the information they need, regardless of its source or format, amalgamated into a single report.

A common solution is to develop software, such as a Web application, that integrates information from a variety of delivery systems. An important task of this app is to integrate and present information from multiple organizational memories. Recently, some organizations have created vast integrated data stores—data warehouses— that are organized repositories of organizational data.

Information integration - the present situation

The ideal organizational memory and information delivery system

Knowledge

The performance of many organizations is determined more by their cognitive capabilities and knowledge than their physical assets. A nation’s wealth is increasingly a result of the knowledge and skills of its citizens (human capital), rather than its natural capital and industrial plants. Currently, about 85 percent of all jobs in America and 80 percent of those in Europe are knowledge-based.

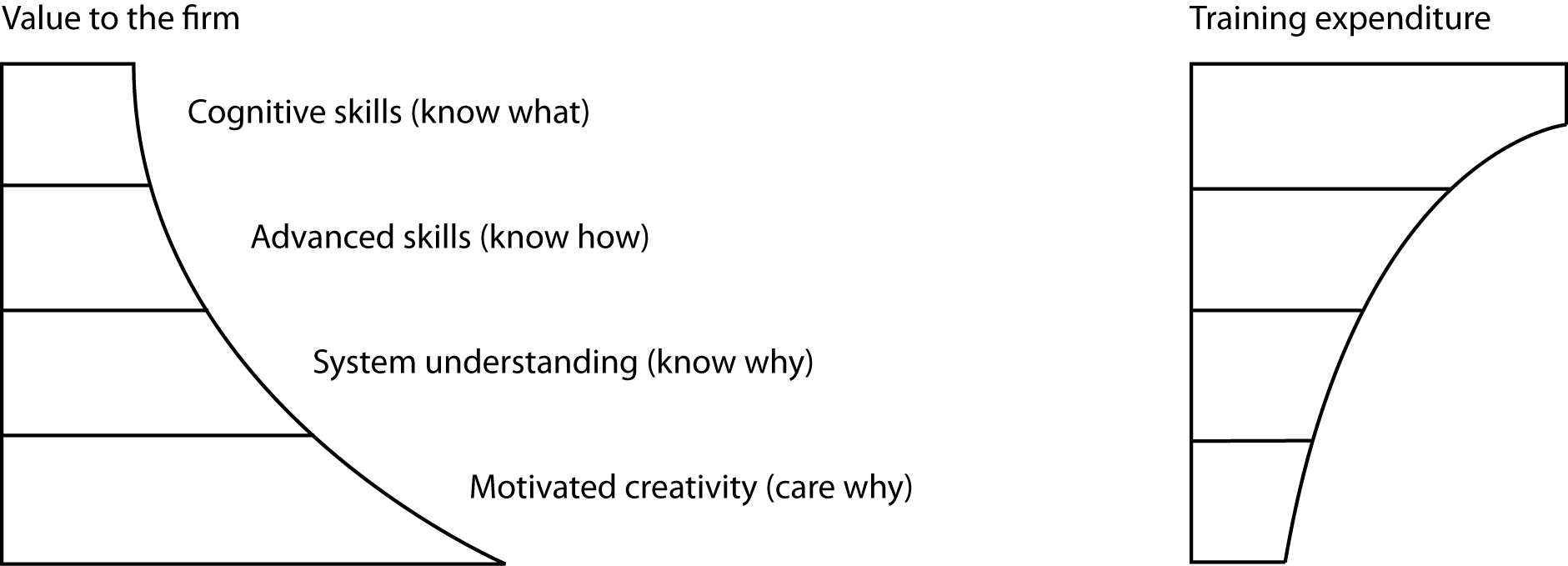

An organization’s knowledge, in order of increasing importance, is

cognitive knowledge (know what);

advanced skills (know how);

system understanding and trained intuition (know why);

self-motivated creativity (care why).

This text illustrates the different types of knowledge. You will develop cognitive knowledge in Section 4, when you learn about data architectures and implementations. For example, knowing what storage devices can be used for archival data is cognitive knowledge. Section 2, data modeling and SQL, develops advanced skills because, upon completion of that section, you will know how to model data and write SQL queries. The first two chapters expand your understanding of the influence of organizational memory on organizational performance. You need to know why you should learn data management skills. Managers know when and why to apply technology, whereas technicians know what to apply and how to apply it. Finally, you are probably an IS major, and your coursework is inculcating the values and norms of the IS profession so that you care why problems are solved using information systems.

Organizations tend to spend more on developing cognitive skills than they do on fostering creativity. This is, unfortunately, the wrong priority. Returns are likely to be much greater when higher-level knowledge skills are developed. Well-managed organizations place more attention on creating know why and care why skills because they recognize that knowledge is a key competitive weapon. Furthermore, these firms have learned that knowledge grows, often very rapidly, when shared. Knowledge is like a communication network whose potential benefit grows exponentially as the nodes within the network grow arithmetically. When knowledge is shared within the organization, or with customers and suppliers, it multiplies as each person receiving knowledge imparts it to someone else in the organization or a business partner.

Skills values vs. training expenditures (Quinn et al., 1996)

There are two types of knowledge: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is codified and transferable. This textbook is an example of explicit knowledge. Knowledge about how to design databases has been formalized and communicated with the intention of transferring it to you, the reader. Tacit knowledge is personal knowledge, experience, and judgment that is difficult to codify. It is more difficult to transfer tacit knowledge because it resides in people’s minds. Usually, the transfer of tacit knowledge requires the sharing of experiences. In learning to model data, the subject of the next section, you will quickly learn how to represent an entity, because this knowledge is made explicit. However, you will find it much harder to model data, because this skill comes with practice. Ideally, you should develop several models under the guidance of an experienced modeler, such as your instructor, who can pass on their tacit knowledge.

Summary

Information has become a key foundation for organizational growth. The information society is founded on computer and communications technology. The accumulation of knowledge requires a capacity to encode and share information. Hard information is very exact. Soft information is extremely imprecise. Rich information exchange occurs in face-to-face conversation. Numeric reports are an example of lean information. Organizations use information to set goals, determine the gap between goals and achievements, determine actions to reach goals, and create new products and services to enhance organizational performance. Managers depend more on informal communication systems than on formal reporting systems. They expect to receive information that meets their current, ever changing needs. Operational managers need short-term information. Senior executives require mainly long-term information but still have a need for both short- and medium-term information. When managers face time constraints, they forced to collect only enough information to make a satisfactory decision. Organizational memory should be integrated to provide one interface to an organization’s information stores.

| Key terms and concepts | |

|---|---|

| Advanced skills (know how) | Information organization |

| Benchmarking | Information requirements |

| Change information | Information richness |

| Cognitive knowledge (know what) | Information satisficing |

| Empowerment | Information society |

| Explicit knowledge | Knowledge |

| Gap information | Managerial work |

| Global change | Organizational change |

| Goal-setting information | Phases of civilization |

| Information as a means of change | Self-motivated creativity (care why) |

| Information delivery systems | Social memory |

| Information hardness | System understanding (know why) |

| Information integration | Tacit knowledge |

Exercises

From an information perspective, what is likely to be different about the customer service era compared to the sustainability era?

How does an information job differ from an industrial job?

Why was the development of paper and writing systems important?

What is the difference between soft and hard information?

What is the difference between rich and lean information exchange?

What are three major types of information connected with organizational change?

What is benchmarking? When might a business use benchmarking?

What is gap information?

Give some examples of how information is used as a means of change.

What sorts of information do senior managers want?

Describe the differences between the way managers handle hard and soft information.

What is information satisficing?

Describe an incident where you used information satisficing.

Give some examples of common information delivery systems.

What is a GIS? Who might use a GIS?

Why is information integration a problem?

How “hard” is an exam grade?

Could you develop a test for the hardness of a piece of information?

Is very soft information worth storing in formal organizational memory? If not, where might you draw the line?

If you had just failed your database exam, would you use rich or lean media to tell a parent or spouse about the result?

Interview a businessperson to determine his or her firm’s critical success factors (CSFs). Remember, a CSF is something the firm must do right to be successful. Generally a firm has about seven CSFs. For the firm’s top three CSFs, identify the information that will measure whether the CSF is being achieved.

If you were managing a quick service restaurant, what information would you want to track performance? Classify this information as short-, medium-, or long-term.

Interview a manager. Identify the information they use to manage the company. Classify this information as short-, medium-, or long-term information. Comment on your findings.

Why is organizational memory like a data warehouse? What needs to be done to make good use of a data warehouse?

What information are you collecting to help determine your career or find a job? What problems are you having collecting this information? Is the information mainly hard or soft?

What type of knowledge should you gain in a university class?

What type of knowledge is likely to make you most valuable?

In late 2021, the four of five most valuable public companies were Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet (Google). Furthermore, these technology giants are concentrated on the west coast of the U.S. in either Silicon Valley or Seattle (source).↩︎

Watson, R. T., Boudreau, M.-C., Li, S., & Levis, J. (2010). Telematics at UPS: En route to Energy Informatics. MISQ Executive, 9(1), 1-11.↩︎

Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness, and structural design. Management Science*, 32(5), 554-571.↩︎

Rockart, J.F. (1982). The changing role of the information systems executive: a critical success factors perspective. Sloan Management Review, 24(1), 3-13.↩︎